Criminal personality Disorder

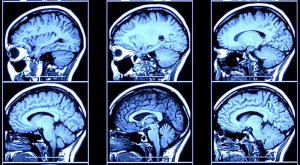

CT scans of a human brain.

CT scans of a human brain.

The latest neuroscience research is presenting intriguing evidence that the brains of certain kinds of criminals are different from those of the rest of the population.

While these findings could improve our understanding of criminal behavior, they also raise moral quandaries about whether and how society should use this knowledge to combat crime.

The criminal mind

In one recent study, scientists examined 21 people with antisocial personality disorder – a condition that characterizes many convicted criminals. Those with the disorder "typically have no regard for right and wrong. They may often violate the law and the rights of others, " according to the Mayo Clinic.

Brain scans of the antisocial people, compared with a control group of individuals without any mental disorders, showed on average an 18-percent reduction in the volume of the brain's middle frontal gyrus, and a 9 percent reduction in the volume of the orbital frontal gyrus – two sections in the brain's frontal lobe.

Another brain study, published in the September 2009 Archives of General Psychiatry, compared 27 psychopaths — people with severe antisocial personality disorder — to 32 non-psychopaths. In the psychopaths, the researchers observed deformations in another part of the brain called the amygdala, with the psychopaths showing a thinning of the outer layer of that region called the cortex and, on average, an 18-percent volume reduction in this part of brain.

"The amygdala is the seat of emotion. Psychopaths lack emotion. They lack empathy, remorse, guilt, " said research team member Adrian Raine, chair of the Department of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., last month.

University of Pennsylvania criminologist Adrian Raine

University of Pennsylvania criminologist Adrian Raine

In addition to brain differences, people who end up being convicted for crimes often show behavioral differences compared with the rest of the population. One long-term study that Raine participated in followed 1, 795 children born in two towns from ages 3 to 23. The study measured many aspects of these individuals' growth and development, and found that 137 became criminal offenders.

One test on the participants at age 3 measured their response to fear – called fear conditioning – by associating a stimulus, such as a tone, with a punishment like an electric shock, and then measuring people's involuntary physical responses through the skin upon hearing the tone.

In this case, the researchers found a distinct lack of fear conditioning in the 3-year-olds who would later become criminals. These findings were published in the January 2010 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Neurological base of crime

Overall, these studies and many more like them paint a picture of significant biological differences between people who commit serious crimes and people who do not. While not all people with antisocial personality disorder — or even all psychopaths — end up breaking the law, and not all criminals meet the criteria for these disorders, there is a marked correlation.

"There is a neuroscience basis in part to the cause of crime, " Raine said.

Criminologist Nathalie Fontaine of Indiana University studies the tendency toward being callous and unemotional (CU) in children between 7 and 12 years old. Children with these traits have been shown to have a higher risk of becoming psychopaths as adults.

"We're not suggesting that some children are psychopaths, but CU traits can be used to identify a subgroup of children who are at risk, " Fontaine said.

Yet her research showed that these traits aren't fixed, and can change in children as they grow. So if psychologists identify children with these risk factors early on, it may not be too late.

"We can still help them, " Fontaine said. "We can implement intervention to support and help children and their families, and we should."

These brain scans of psychopaths show a deformation in the amygdala compared to non-psychopaths, from a study by Adrian Raine and colleagues.

Credit: Yang et al./Archives of General PsychiatryNeuroscientists' understanding of the plasticity, or flexibility, of the brain called neurogenesis supports the idea that many of these brain differences are not fixed.

"Brain research is showing us that neurogenesis can occur even into adulthood, " said psychologist Patricia Brennan of Emory University in Atlanta. "Biology isn’t destiny. There are many, many places you can intervene along that developmental pathway to change what's happening in these children."